Bodywork: Reforming ’90s in Contemporary Fashion

From the start of my editorial residency at Topical Cream, I’ve wanted to invite curator and writer Alexandra Cunningham Cameron to write on a topic that we have discussed many times, and one that I knew she could delve further into: the resurgence of ’90s style. Cunningham Cameron brings a key perspective to this subject because of the extensive research she conducted in preparation for her groundbreaking 2020 exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt, Willi Smith: Street Couture, offering valuable insights into the unique conditions that have shaped this resurgence. For many years, we have been in dialogue around interdisciplinary practices, artists who delve into fashion and design, designers who delve into art, etc., and I am very honored to have been able to commission this text, which needed to be written, and which says so much about today by critically piecing together a short history of recent fashion and cultural shifts.

– Ruba Katrib, 2023 EIR

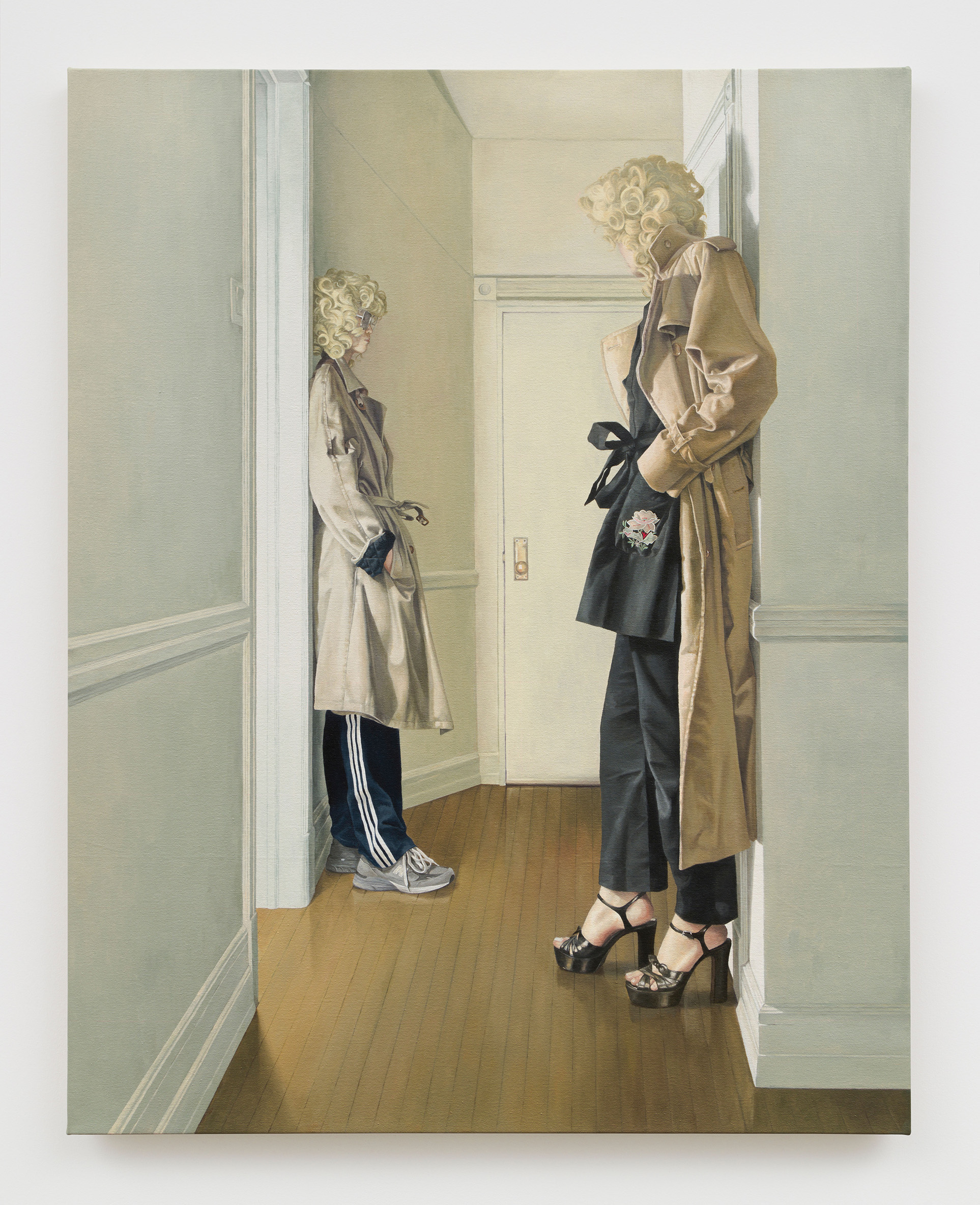

The shape of American bodies changed after the 1990s. I thought this while standing in Lubov Gallery looking at Eunnam Hong’s paintings of femme forms slouching like Deborah Turbeville mannequins in Chungking Express wigs. What was it? Not exactly the body itself. Something more than the physical implications of surgical innovations or CrossFit or metabolic dysregulation from fast foods and screen sitting. Less formal, more attitudinal. It was the wistful lean against the wall that draped the trench over the track pant. Hong’s 90s fits on contemporary frames felt just out of proportion, the same but different, like a Balenciaga Ikea bag.

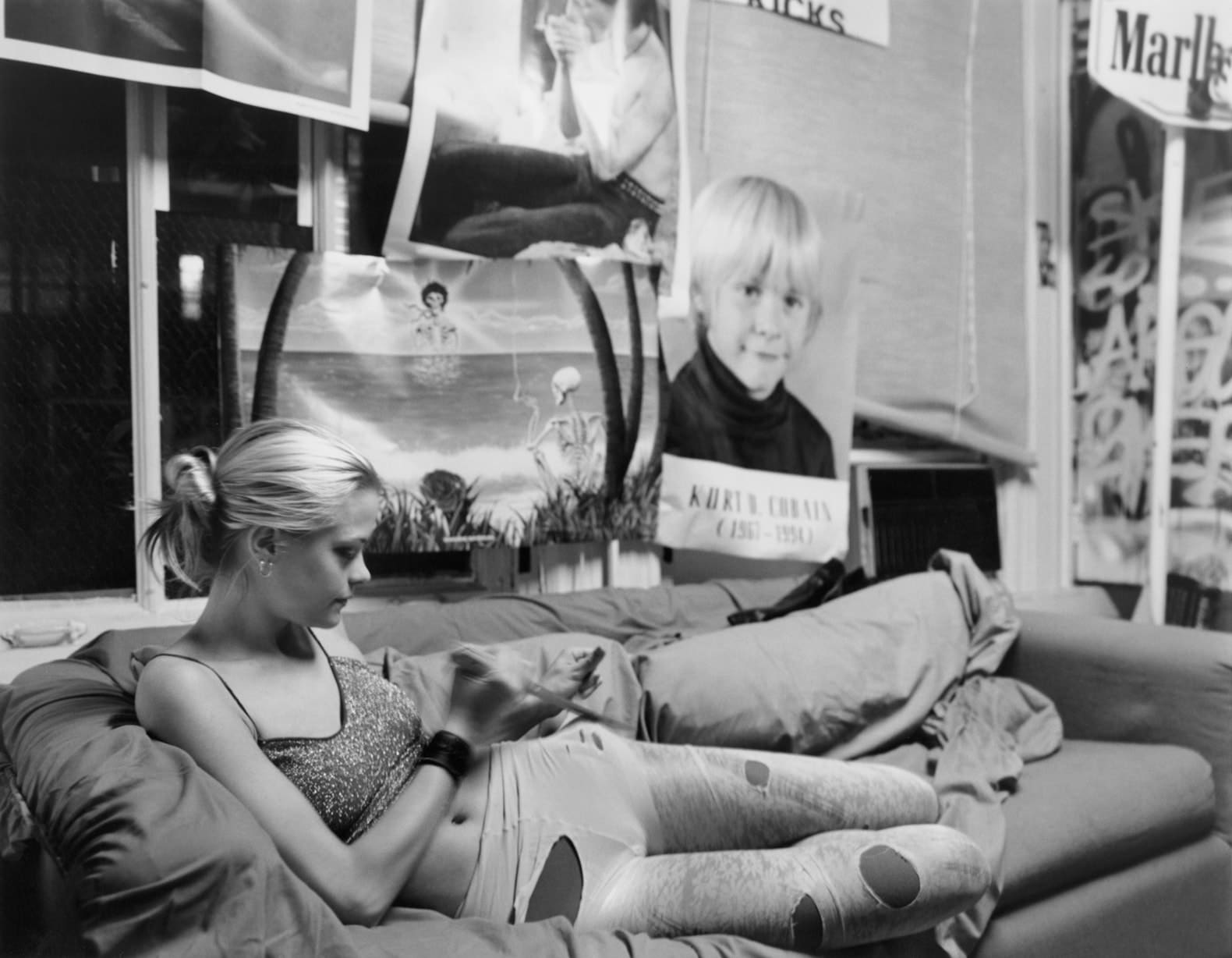

Now, you see it everywhere, the ’90s fashion revival on 2020s bodies. JNCOs and slips coming around the street corner. Varsity color-block billboards. Y2K camp. The unique-piece assemblage work of a new school of designers. I took notice when Liz Goldwyn staged an online auction of her Run collection. Fifty-eight garments Susan Cianciolo made between 1995–2001 posted on Liz.run, an early-internet anti-design styled ecommerce cum archive. Each thready ensemble is modeled by younger fans and accompanied by confessional storytelling about the life of the garments and the exploits of the time, a voyeuristic ode to Cianciolo’s esoteric social practice. The site seemed packaged less for nostalgia-seekers who peaked in the ’90s and more for a new-form generation, conceived—biologically, philosophically—in the ’90s and matured today with unprecedented access to knowledge and a complicated relationship with boundaries, disciplinary or otherwise.

We are crossing in the ’20s, as we did in the ’90s, a bridge between old and new worlds—a paradigm shift that marks a new model of creative being. Each decade a portal shaped by unprecedented economic booms, widening wealth disparity, the disorientation of pandemics, AIDS and COVID, amplified by the web’s accelerating streams of communication. Confrontational relationships with abortion, guns, addiction, surveillance, censorship, climate, identity, and entrepreneurship give way to new expressions, new experiments, unfolding out of the paradoxical sense that there’s both nothing and everything to lose.

The ’90s and ’20s bookmark an accelerating awareness of audience—progressively digital, data-driven, commercial—that, at first, caused a sort of vigilance as we noticed the impact of our impressions on the world, the opportunities of the nascent experience economy, but ultimately sobered into an atmosphere of artifice and self-censorship. As it’s developed in the past 20 years, as algorithms have smartened and truth has sussed, the feedback loop has bred bland mimetic tendencies, iteration, buoying communal style, quick trend waves, fast fashion, softening the poignant otherness of countercultures. Even the influencers have become bored by their influence as we’ve spent the aughts becoming immersed in each other, an American-feeling idiosyncratic synchronicity of visual references quilting together.

This compounding of culture and commerce began, in part, with three seminal launches between 1982–3:

Dapper Dan opened his eponymous boutique in Harlem, selling unique and custom garments reimagined from deconstructed Gucci, Fendi, and Louis Vuitton. His practice emerged alongside the rise of Hip-Hop-adjacent style movements in Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Bronx that remixed luxury and athletic brands into utilitarian and affirming ensembles. When musicians like LL Cool J, Salt-N-Pepa, and Eric B and Rakim started wearing his designs, the fashion-industrial complex observed the influence of Black artists in mainstream markets. Dapper Dan’s success was a key plot point in the long story of brands commodifying Black American expressive culture, but also opened the doors for diverse fashion businesses to operate on their own terms.

The next year, WilliWear templated the boundary-breaking brand campaign by fusing ready-to-wear with art, music, video, and communication design for the Fall 1983 Street Couture collection, presented in a runway event held at New York’s Puck Building. Techno-utopian Juan Downey flanked the runway with a twenty-eight-channel video work, post-punk composer Jorge Socarras produced an original score, and new-wave graphic designer Bill Bonnell created a unique visual identity for the collection. The collaborations were bolstered by the energy of the still new contemporary art market, but also decidedly synergistic, driven by a shared desire to connect art and everyday life, an extension of Willi Smith and Laurie Mallet’s relationships with downtown artists employing products and commerce as material and interest in bringing street style and queer culture into the mainstream.

“We are crossing in the ’20s, as we did in the ’90s, a bridge between old and new worlds—a paradigm shift that marks a new model of creative being.”

Then, Ralph Lauren launched his first Home Furnishings collection, establishing fashion’s ability to reach beyond the closet and dictate how people lived and leisured. Ralph Lauren Home translated cultures, geographies, and fantasies like Log Cabin, Thoroughbred, Jamaica, and New England into aspirational, colonial décor for Americans with disposable income. Lauren anticipated the explosion of conspicuous consumption produced by the decade’s atmosphere of economic optimism and new media marketing. It totalized the reach of a fashion brand into the lives of its consumers, and formalized the potential for fashion designers to successfully cross over disciplinary borders.

By the ’90s, American fashion and lifestyle were nearly interchangeable categories, defining the decade with commercial expressions and appropriations of countercultural movements and diverse experiences. Self-taught, celebrity, and artist-founded brands like Sean Comb’s Sean John, Kim Gordon’s X-Girl, Daymond John’s FUBU, Don Busweiler’s Pervert, April Walker’s Walker Wear, Laura Whitcomb’s Label, Sofia Coppola’s Milk Girl, Jordan Bettan’s Lost Art, and Wu-Tang Clan’s Wu Wear epitomized the internet era’s embrace of polymathic entrepreneurship and unraveling of academic expertise across creative fields. Creative agencies like M/M Paris solidified brand campaigns with artists, designers, and writers while a new era of fashion media—Purple, i-D, Flaunt, Six, Detour, Visionaire—created a new lens through which to understand fashion culture. The groundwork laid by Dapper Dan—proto-influencer marketing through music, then sports and cinema—upended traditional advertising, as he was overwhelmed by IP litigation and forced to cease operations.

Out of any decade of the twentieth century, the ’90s was most densely packed with conceptual fashion projects that redrew aesthetics in service of identity. A range of practices proliferated in the underground, driven by a DIY ethos, often forming collectives to consolidate resources, skills, and perspectives. Informed by visual and performing artists, costumers, adaptive reuse, and craft traditions, these hybrid voices often sat outside the system, eschewing corporate greed while relying on novel models of patronage to support their work. In New York alone, Bernadette Corporation, Miguel Adrover, Cianciolo, The Organization for Returning Fashion Interest (ORFI), Imitation of Christ, and Three As Four emerged as examples of fashion’s détournement.

The expanse of this ’90s rebellion against the traditional fashion system continues to be under-appreciated in establishment histories, which, despite recent efforts to expand the canon, prioritize the practices like the Antwerp 6 who eventually succeeded in luxury markets. Colleen Hill’s 2022 Reinvention and Restlessness: Fashion in the 90s via FIT provides the only remarkable survey of the decade. The currently on-view 1997 Fashion Big Bang at Pallais Galliera—Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris focuses on the European designers who anticipated the commercial explosion of global fashion at the new millennium. Other efforts to parse the decade emphasize the eye of the photographer interpreting a shift in ethos, or rely on the storytelling of provocative collections from industry giants like Rei Kawakubo, Christian, Lacroix, Thierry Mugler, or Jean-Paul Gaultier.

It’s possible that the shock of 9/11 created too deep of a wound for the interdependent, polyvocal movements happening in the ’90s to formalize. Momentum was already faltering at the dawn of Y2k as Bush-dynasty culture wars ignited and H&M opened its 5th Avenue flagship. After the World Trade Center collapsed during New York Fashion Week in 2001, the industry rallied in support of suffering brands by formalizing structures, like the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, to bring young design studios into the commercial system. The effort launched careers and fostered brands like Proenza Schouler, Rodarte, and Derek Lam, but the emphasis on marketability further bifurcated alternative and commercial practices. Pockets of outsider creativity waned. The industry’s historical lack of investment in BIPOC-owned brands persevered. Beyond the spree of expression post-2008 recession, the normalization of luxury goods and the explosion of fast fashion through arts and influencer marketing characterized the aughts, resulting in environmental, economic, and racial precarities that have fatigued consumers and frustrated designers. Is there a good choice between a $300 and a $5 T-shirt?

Reactions to this need for a new way forward reignited interest in ’90s-modeled DIY community collaboration, aesthetics, and entrepreneurship in critical design circles even before the pandemic swelled, shops closed, shows canceled, and business models were reimagined. But the peak saturation of ’90s references that ensued conveys less of an homage to a sister decade and more of a durable transformation in the creative body of the designer (if not yet fashion business).

In a recent talk at the Leslie Lohman Museum to inaugurate Viscose ISSUE 4: TRANS fashion, self-fashioning came up as a process that still lives outside the fashion system; the Euro-canonical determinants of quality—such as form, cut, and silhouette—exist at odds with the subversive work of design in service of subjectivity, mobility, and justice. If this division still rings true in fashion studies circles, it doesn’t play out in contemporary practice. Progressive fashion projects proliferated in the ’90s because the decade embraced social context and reconsidered expertise. From the popularization of Cultural Studies to relational aesthetics, the move to represent diverse experiences developed alongside the growing understanding of the self as a node in a network. The penetration of fashion art and commerce into lifestyle magnified by mass media and new internet connectivity enabled a complexity of voice to take hold in a way that previous decades of fashion resistance could not.

“Out of any decade of the twentieth century, the ’90s was most densely packed with conceptual fashion projects that redrew aesthetics in service of identity.”

Our decade, three years in, at the intersection of culture wars, AI, and Web3, has opened a new portal for model change. The momentum of the ’90s, despite its disrupted trajectory, seems to be culminating now in an accountability of voice that resists exclusion, conformity, and capital through designs dedicated to liberation, community, and difference that fundamentally collapse technique with critique. The most novel fashion practices working today represent a new form of designer, most born digital, who advance discourse through visual justice. They illustrate (and sometimes pander to) a deep understanding of our interconnectivity. They converse with history, with audience, with politics, with materials, with nature, and with other makers. They don’t just design garments, they design furniture, environments, communities, and futures. Their practices are social, multidisciplinary, and public-facing. U.S.-based designers such as CFGNY, Camilla Carper, Zoe Gustavia Anna Whalen, Sc103, Barragán, Elena Velez, Lou Dallas, Gogo Graham, WILLIENORRISREWORKSHOP, and Taofeek Abijako, to name a few, are resolving what began in the ’90s into a new model of creativity—wielding the materials of our time to know each other, as Baudelaire writes, rather than ourselves, through a new aesthetic language.

Behind today’s layers of ’90s-era commercial camp lies a new designer conditioned by a new playing field that was prototyped thirty years ago (and thirty years before that by Black Arts Movements, and thirty years before that by the Futurists, and on). Today’s avant-garde express the chaotic interdependence that defines contemporary experience by camouflaging the body in a sort of dazzle-wear, employing collage, thrift, humor, salvage, and trompe l’oeil that morphs from body to space to object to pixel and back again. Their dense textures and allusions rail against inescapable surveillance, mass-manufacture, delirious data, flattened digital forms, and categorization while participating in versions of an independent (fashion) economy. They protest while acknowledging the apparent futility of protest—one of the many forms that illustrate this generation of creators inextricably reliant on the tools of capital to realize dreams of equity.

Alexandra Cunningham Cameron is curator of contemporary design and Hintz Secretarial Scholar at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.