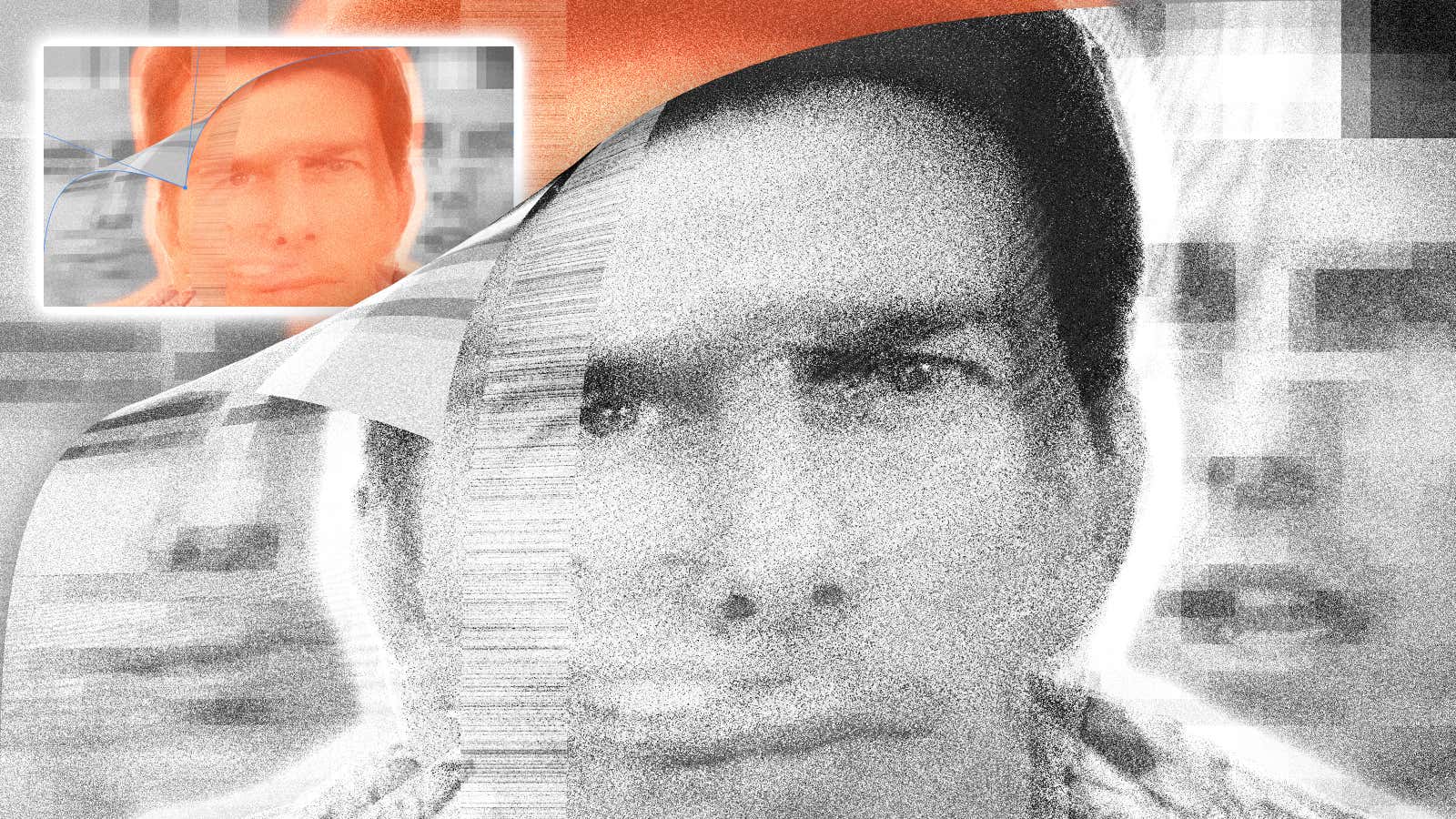

On TikTok, you might have seen Tom Cruise playing acoustic guitar in a plain white t-shirt and a green baseball cap. You might have seen Tom Cruise check himself out shirtless in a bathroom mirror. Or playing golf in a white Polo shirt and fedora.

But Tom Cruise isn’t on TikTok.

All of these Tom Cruise appearances were deepfakes, computer-generated videos that transplant a person’s face, voice, and overall likeness onto another body (in this case, actor Miles Fisher).

Almost everything about deepfakes is controversial. The term, a mishmash of “deep learning” and “fake”), originates from a Reddit community in 2017 that retrofitted pornographic videos with celebrities’ faces on them, causing an ethical row around the technology. While manipulated videos didn’t originate on a subreddit nor did fake celebrity porn, the ordeal brought deepfakes—the term as well as the concept—to the forefront of ethical tech debates.

In an age of rising misinformation and cyberattacks, the most worrying risk around deepfake technology is hostile political propaganda, potentially sparking protests or violence. One recent study (pdf) from researchers at Harvard, Penn State, and Washington University in St. Louis shows deepfakes can convince about half of those who view the material of fake political scandals, “alarming rates” on par with fake text headlines and audio clips.

Social media platforms are already preparing for another powerful tool to manipulate the information ecosystem. Since Jordan Peele’s deepfake video of Barack Obama in 2018, Twitter and other social media sites have introduced mandatory labeling for synthetic media. That hasn’t dented their popularity. The account Deep Tom Cruise racked up 3.3 million TikTok followers.

It’s convincing stuff—Tom seems to bypass the “uncanny valley,” the unsettling middle-ground between human and humanoid faces. The firm behind Deep Tom Cruise is called Metaphysic, led by co-founders Tom Graham and Chris Ume, and it just raised $7.5 million in a seed round led by Section 32 and includes the Winklevoss twins and YouTuber Logan Paul. Quartz spoke with Graham about the company, the case for deepfake technology, the metaverse, web3, and of course Tom Cruise.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is Deep Tom Cruise?

DeepTom Cruise stuff is an art project—a collaboration with the performer Miles Fisher to raise awareness around hyper-real deepfakes that could lead to misinformation or some kind of harm to users. Deep Tom Cruise became the iconic inflection point for hyper-real media. It was really the first time that people had been genuinely confused and millions of people had wondered at first glance, “Is that Tom Cruise?” The intention was never to deceive them, and it was clearly labeled as manipulated media footage should be, but the impact was really quite profound. A lot of people have built negative connotations around the term deepfakes, which is really kind of a very small subset of synthetic media. Instagram filters rely heavily on A.I. to change faces. That’s synthetic media. Big content creators like Disney use this kind of technology—South Park uses it. A lot of synthetic media on the audio front is deployed into podcasts without anybody ever really knowing it.

How are you thinking about deploying deepfakes ethically?

Deepfakes have been characterized as potentially negative—mostly because of the potential for political misinformation. There are particular vulnerabilities for small countries with fragile democracies where a particularly ill-intentioned leader might try to control information flow or denounce his opponent or something like that.

The other issue is digital sexual violence, predominantly against women, in some kind of revenge porn or deepfake face-swap pornography, which is deeply disturbing. I think everybody in the industry developing the technology is quite diligent, actively and responsibly thinking about how they deploy and develop the technology and who they make it available to combat exactly those types of harms.

How do we get to a place where we can use this technology responsibly?

The most salient point is around consent. We will only work with consent for commercial kind of stuff—synthetic media projects for commercial purposes—where there’s consent of the person whose synthetic likeness is being created, and that’s widespread across the industry. And then there is the idea of having a web3 layer where you or I own our own data and that data is used to create a synthetic likeness of us. It provides a kind of auditable, transparent mechanism for us to give consent to a third party like Zoom or Microsoft or Activision—whoever is going to create the content, or put us inside the content experience in the future.

We would like to imagine a world where it’s difficult for people to use this kind of really important biometric data. We think blockchain technologies are pretty good at doing that and they couple that with economic incentives. If you have a good way of paying tens of millions of people, maybe small micro-transactions, small amounts accrue over time. I think that’s a boon for people building products in the future, especially when these products rely on a large amount of data.

Who needs to give consent in these circumstances? The people being imitated?

Yeah, the consent of a person whose synthetic likeness is being recreated. If you put that into the context of a famous actor, if they don’t want to be in a movie, they just don’t turn up. So how do you withhold that consent in a virtual environment where suddenly someone has your data, and it doesn’t take a huge amount of data in order to create a synthetic representation of you?

It is relatively difficult technology but it is becoming easier and easier like all technologies. There are hardware bottlenecks in terms of what you can do, bandwidth issues, it takes a large amount of data and a lot of money. There are barriers to entry that will be reduced over time. And so we have a certain period in order to set up like a set of norms and standards where the user and consent are really at the forefront. People building products, technology companies, open-source developers, hobbyists, people building stuff all need to really think about the human experience of content in the metaverse.

Did you have Tom Cruise’s consent to do Deepfake Tom?

It actually started as kind of like a collaborative art project between Chris Ume, my co-founder, and Miles, the actor. We reached out to Tom Cruise’s team many times and eventually heard from them, but they didn’t have any specific comment either way. So we offered to give them ownership, input, the opportunity to say they didn’t like it and eventually, they came back and had no specific comment, which is fair.

There is a lot going on there around consent also, which I think requires a nuanced discussion because in the technology world, you’re talking about relatively powerful actors building products dealing with regular users in a commercial kind of setting. But there are lots and lots of instances where people create content where, from a free speech point of view, from a Western liberal democracy point of view, it’s really important that people are able to speak truth to power to create commentary, parody, and satire. I don’t think Deep Tom Cruise is political parody, but I think it is an important element of our society that we are able to create things like that. That plays into fair use and freedom of speech-type things.

What’s your business right now? Who are you selling to?

We are leaders in the space of creating hyper-real synthetic media. Where do you find that kind of media today? Generally, because it’s relatively difficult, it’s high-value content: movies, advertisements, commercials, TikTok-inspired social content on behalf of somebody with really high-value IP or someone with lots of followers.

We also use those commercial projects to feed our technology development pipeline so that sometime relatively soon we can scale out the ethical creation of hyper-real content experiences to users at an internet-scale. We could be doing this phone call as our hyper-real selves. You could imagine yourself going to the metaverse cinema to watch Tom Cruise’s Mission Impossible 7 or 12 and it’s a fully immersive kind of like game, a hyper-real experience. And suddenly you’re playing one of the characters, or instead, you take a step back and you become one of the extras.

Your vision of the metaverse seems predicated on blockchains tracking ownership and consent. Is this possible without blockchains?

I think on one level, your question is predicated on a vision for the metaverse that has unfortunately been co-opted by gamers plus monoculture tech like Ready Player One. When people think about metaverse, they think of game-like avatars running through this game world and you can do whatever you want. When I think about it, it’s a multi-platform metaverse where it’s not real life, but it’s deeply emotionally engaging, rewarding experiences among communities online.

I look at TikTok. You see people playing all kinds of characters and then people dueting them and then making their own content on top of that [editor’s note: a duet on TikTok is a video response to another video]. There’s a real ecosystem around content and human connection and entertainment and engagement there, which doesn’t have any kind of crypto layer or anything like that. That, for me, creates like mini little metaverses. You can think of DeepTom Cruise on Tik Tok as its own kind of parallel universe for like what Tom Cruise could be if he were mid-30s and TikTok came along and he decided to do lots of irreverent content.

Ready Player One was not predicated on any crypto background—it was one big centralized company. So in that kind of dichotomy between closed and open metaverse, I think that ultimately open web3 metaverses will gain the same kind of traction as closed system metaverses. Maybe Facebook is a closed system and then they allow interoperability with open systems. But because of the ability to attract developers, create interesting content, and participate more directly in the economics—so like the direct connection of users and their money through to attention and content creator with no intermediary, with no kind of like Big Tech company in the middle, that just creates so much economic incentive that I think it’s impossible that those open platforms don’t really explode and flourish.

Zooming out, why should we want deepfake versions of ourselves? Why can’t we look like robots or legless cartoon avatars in the metaverse?

We have the potential to be whoever we want in the metaverse at any point in the future. But if you look at standard tropes of human behavior, take online dating, for instance. We spend a lot of time putting on makeup, preening our appearance, making ourselves look good through photos on a Tinder profile, or something like that. And we make all of that effort to modify and manipulate the way we appear online to somebody else. But we don’t make ourselves into robots or we don’t give ourselves horns. It probably takes a really long time, but also it’s just not like a standard human behavior. If we take that kind of logic across to say, online shopping, if you are trying on a jacket or a dress inside the online metaverse Gucci store, you’re not going to want to try it on as a dragon or a crazy space cow. Because what we do in the metaverse can have real-world implications.