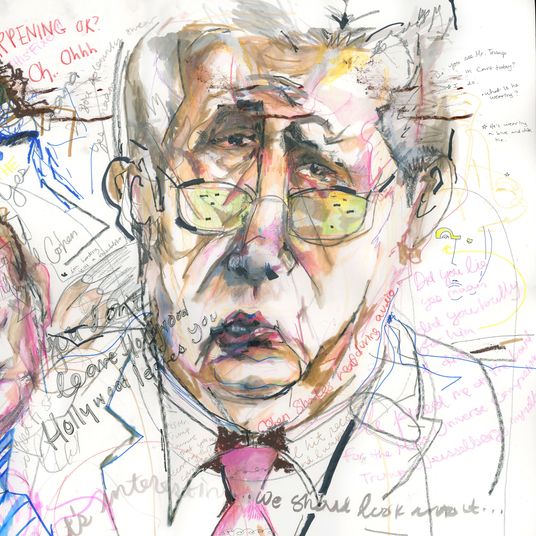

I’m often thinking about Balzac,” Mike Crumplar, a 30-year-old recently lapsed Substacker tells me in the backyard of a bar in Greenpoint, a cigarette in one hand and a pilsner in the other. “My New York is his Paris. There’s a lot of the same scene shit and intrigues — dramas and fights over poetry and bourgeois illusions and shit.”

There’s a good chance that you’ve never heard of, much less read, what the writer called his Crumpstack, a word that has no known French translation. In it, he sought to depict, and send up, the world of hard-tweeting, coke-snorting aspiring rebel intellectuals who hung out in a made-up mini-neighborhood called Dimes Square during the COVID lockdown. (Crumplar himself moved to New York from Washington, D.C., in January 2022.) His newsletter, a kind of diary, mixing essays, score-settling, and party reportage, had around 7,000 subscribers, which might very well have exceeded the entire population of that milieu, where it was avidly hate-read. But as many clout-chasing arrivistes have found before, from those who wrote for the gossip rags of Balzac’s 1830s Paris to the Gawker bloggers of the aughts, the surest way to make a name for yourself is to mock those who came before you.

Crumplar sought to speak truth to niche social power. Some of what he wrote was snarky fun. (He called Dimes Square “a place where older literary men can have younger muses, free from the prudish Robespierres of the North Brooklyn DSA.”) He labels many of his “characters” — real people — “fascists.” Fascist might be overused these days, but there is in fact a defiantly reactionary current downtown. Many of its leading figures consort with the likes of James O’Keefe (who once appeared in Crumpstack reading from Henry V at a party), blogger Curtis Yarvin, Peter Thiel (who underwrote an “anti-woke” film festival), and even Alex Jones (who has appeared on the Red Scare podcast). Some fixtures, like the writer Honor Levy, like to go on about their adoption of traditionalist Catholicism. Crumplar has said he is “committed to radical-left politics” and sought to call them out.

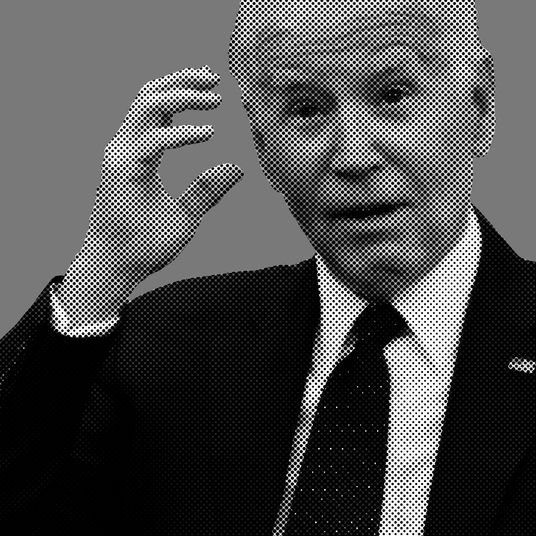

In person, he can be a difficult conversationalist, drifting into overintellectualization and conspiratorial thinking. He starts more sentences than he finishes, rarely makes eye contact, and is usually, in the course of his monologuing, scratching his eyebrow or the back of his head.

And while I’m not sure anybody would confuse his prose with Balzac’s, in certain ways he is ballsy. When Air Mail put him on its “Downtown Set” list of “50 Young New Yorkers Remaking Lower Manhattan in Their Own Image” last year, it wrote, “Every regime has its gadfly, and Dimes Square has Mike Crumplar.” The most memorable Crumpstacks describe confrontations, which he seems to thrive on. In one, he wrote about the indie filmmaker Peter Vack inviting him to a shoot with scenesters who hated him for what he’d written about them, including Red Scare podcast host Dasha Nekrasova and the actress Betsey Brown. They all roasted him on-camera, and he wrote that it was his “Dimes Square Fascist Humiliation Ritual.” Another post, called “All in Good Fun,” recounted his being denied entry to a literary event unless he let Nekrasova slap him. The video got passed around widely, and I can tell he kind of loved it. “She was in a weird way rewarding me for being relevant,” he says. He seems to think it was sort of sexually charged.

At some point in our conversation, he says, “In a lot of ways, I’m just embodying this boring bourgeois white dude subjectivity,” without further explanation. But I think I know what he means.

By day, Crumplar is a copy editor, working on reports for the World Bank and the U.N. with colleagues who don’t know about his nocturnal notoriousness. He grew up in suburban Virginia, and his father, a former Navy man, is a defense contractor. At William & Mary, he majored in German studies (“Reading Nietzsche and stuff”). College is also where he got his nickname, “Crumps,” from his fraternity brothers, whom he now also describes as “fascist Republican people.”

“I have a weird relationship with my family,” he says. “They’d rather me live in D.C. and work for the State Department or something.” His job went remote during the pandemic, which allowed him to move here. Living in D.C., he felt “socially isolated,” so it was thrilling to be in New York, where “people were constantly having parties around their poetry readings,” he says. “That was foreign to me. So exotic.” Plus there were better drugs: “There’s fucking psychedelics everywhere. Everyone is doing it.”

In early September, Crumplar announced he was stepping back from Crumpstack, sharing on Instagram that he would be “reevaluating my values and how they’re expressed in my work.” He says he felt he’d gotten too cozy with the crowd that he had moved here to critique. Soon after, his close friend, a woman named Tai who has styled herself as 2023’s Valerie Solanas and appeared frequently in his writing, took to her own socials and turned on him: “The fascists slob on your impotent cock because you give them free gossip press.” Another of his newly empowered characters tweeted ominously that “there is a big reckoning for the Dimes Square scene coming soon in which people will have to actually consider its historical political significance,” also writing that “Crumplar … was willingly or unwillingly complicit in the ‘fascist’ project happening.” (One of his readers, talking about a young writer he covered, once told me, “She was in the fucking Crumpstack … He made her a figure. That’s power!”) Also, and maybe because he likes to microdose acid on the job, he admits he’s gotten some things wrong. But he never claimed to be a journalist, exactly. This is more a serialized novel. (Balzac: “Journalism is an inferno, a bottomless pit of iniquity, falsehood and treachery.”)

Crumplar leaves open the possibility of his return from Substack exile. Still, he admits, “I definitely think it’s true that I was kind of on an ego trip. I got lost in the sauce or whatever. But I’m going to come out of that having some distance and a book that kicks ass.” Complicity, he says, was the price of admission. “You’re not rooting out the evil if you’re getting wrapped up in it,” one of his many frenemies tells me.

Eventually, after several beers, Crumplar and I set off to a party down the street in a loft where Matthew Gasda, who wrote the underground play Dimes Square, in which members of that scene played versions of their louche selves, stages his work. Crumplar last year panned that play — “It would be nice to have some art that does more than tickle the enjoyment of seeing oneself in the cocaine mirror” — but has since revised his opinion of the playwright. “He’s like a neurotic misogynistic tyrant or a fool,” he allows. “But he was also a three-dimensional character that’s absurd and sympathetic in certain ways.” Tonight is a celebration of Gasda’s latest, Zoomers, a dramedy about two kids who “find themselves adrift in the social landscape of New York.”

Everybody I talk to at the party seems appropriately adrift, fretting about their creative endeavors and wondering aloud if they really are their generation’s Warhols. (According to Crumplar, the only Factory-ready people around are Nekrasova and Caroline Calloway, whose memoir he helped edit.)

The thing is Dimes Square, despite the hoopla, has yet to have widespread influence. As Jack Antonoff recently told The Face, “What’s the book, what’s the band? The toxic podcast can’t be the genius cultural export.” Crumplar would nominate his Substack.

“The point I’m at right now is basically in Balzac’s Lost Illusions where Lucien has fallen on his face,” he says. “This naïve, idealistic writer goes to Paris and gets immersed in the city and kind of gets chewed up and spit out by it.”