As the horrors mounted in Israel and Palestine, in America we did what we do best: We issued statements. Then we found fault with those statements and issued new statements.

At Harvard, a coalition of pro-Palestine student groups signed a statement holding Israel “entirely responsible” for Hamas’s attack before its full and horrific dimensions could even be known — and before administrators had managed to issue their own statement, which, in turn, proved too

neutral for dozens of pro-Israel faculty members, who published an open letter, prompting another statement from Harvard’s president, Claudine Gay, which more explicitly condemned Hamas’s “terrorist atrocities.” Similar cycles of statement and restatement played out at NYU, Stanford, and Indiana University.

The situation became so fraught at Williams College that its president, Maud Mandel, announced she would no longer be making any statements on any domestic or international matters. “I have become convinced that such comments do more harm than good,” she said. “They support some members of our community in particular moments while intentionally or unintentionally leaving out others. They give some issues great visibility while leaving others unseen.”

But it wasn’t just college campuses. Statements rushed in from every corner, from politicians and business leaders; from brands and celebrities; from professional sports franchises, venture-capitalist firms, and labor unions. Every new statement was an opportunity for scrutiny, for dissatisfaction, for rancor. Even ordinary people, I noticed, seemed to adopt the rhetorical tics of statementese, as if their social-media posts, too, were being written by committee, in consultation with crisis managers, calculated to assuage several constituencies: “My heart goes out to …” “While I strongly condemn …” “Two things can be true at once …” “We here at Sam Adler-Bell’s Twitter account …” And when these statements, inevitably, were found wanting, we condemned them too.

We are accustomed to this ritual. It is familiar and, in this sense, something of a comfort. We distract ourselves, momentarily, from the real stakes of ongoing catastrophe by getting angry at college students, at Justin Bieber, at strangers on the internet. We fixate on words, invest them with talismanic power; perhaps, in the right combination, they can stop the bombs, make sense of so many deaths. In many debates, the crucial question seemed to be not “What is to be done?” but “What is to be said?”

These arguments exhaust me. Of course, words matter (here I am, using them now). But all this wrangling over diction, emphasis, and affect has begun to feel monstrously trivial. While I was writing this essay, a bomb exploded at a hospital in Gaza, killing hundreds. Hamas blamed Israel; Israel blamed a wayward rocket fired by Palestinian militants. About 1,400 Israelis were killed in the October 7 attack; the death toll in Gaza has surpassed 4,000.

Why, I wonder, does this conflict so often play out, in the U.S., as a conflict over words? An unavoidable answer is that the custodians of America’s pro-Israel policy consensus have long treated certain words — like apartheid, genocide, and even Palestine — as existentially threatening. For decades, it has been the explicit mission of pro-Israel groups to disallow certain kinds of speech, conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism. Conservative millionaires who wailed for years about “cancel culture” and the censorious left today are pressuring colleges to release the names of students who signed pro-Palestine letters to blacklist them from future jobs. If words are as dangerous to the status quo as Israel’s fretful apologists seem to believe, perhaps using the right ones could matter a great deal.

And yet hasn’t Israel made itself strong enough to withstand the threat of mere language? As we have already seen in this war, Israel will not be hindered by words, even those written down in international law. It strikes me that part of our fixation on statements derives from a sense of helplessness. You can’t stop Israel from starving and bombing the people of Gaza, nor prevent your own government from supplying the weapons and treasure to do so. But you might be able to get your kid’s school district to release a better statement on the matter.

This frustration is real. In Congress, where a robust debate about the posture of the U.S. toward Israel’s increasingly brutal siege — about the means at the Biden administration’s disposal to protect civilians and de-escalate the war — is sorely needed, a very small range of opinions have been deemed acceptable. The vast majority of elected Democrats have followed Biden’s lead in backing Israel unconditionally in public. Despite rising evidence of indiscriminate attacks on civilians, Biden has promised an unprecedented influx of military aid. Just 13 members of the House, led by Cori Bush of Missouri and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, among others, have called for a cease-fire — a demand for stanching the bloodshed that the White House deemed “repugnant” and “disgraceful.”

When our government is this unresponsive, it makes sense that Americans look closer to home for moral clarity. Powerless to influence actual policy outcomes, we settle for battling over discourse.

But how helpless are we, really? On X, the political theorist Corey Robin recently noted “the passivity of the verbs we so often use now, all of which are oriented to the pastness of things, as if action is something that already occurred, not something to be done: ‘witness,’ ‘acknowledge,’ ‘mourn,’ ‘grieve,’ ‘testify,’ and so on.” I’ve been struck by this too. Statementese is a past-tense idiom — lamenting from afar what cannot be stopped, what has already come to pass. It produces helplessness even as it is conditioned by it.

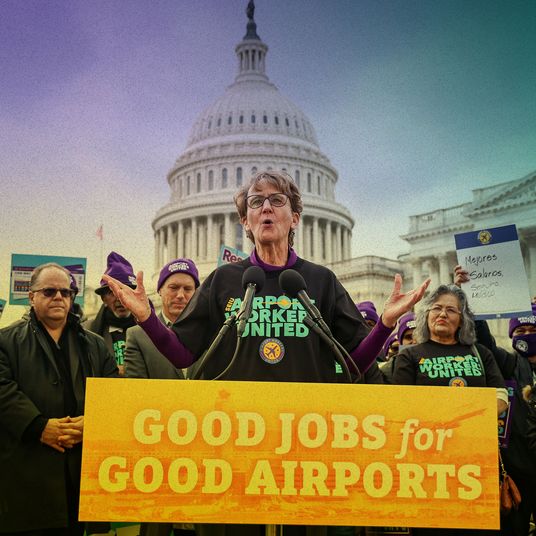

For Americans to submit to helplessness, however, is a moral perversion. The lever of U.S. policy could be decisive in shortening this war and mitigating its suffering, and we — unlike the Palestinians — have a representative government that is, at least in principle, responsive to our democratic will. On Wednesday, thousands of young American Jews convened at the Capitol to demand a cease-fire; hundreds, including two dozen rabbis, were arrested at a peaceful sit-in inside the rotunda. “In the face of unspeakable, genocidal horror and cruelty,” said Eva Borgwardt, national spokesperson of IfNotNow, an anti-occupation Jewish organization, “Jews are descending on the Capitol by the thousands, refusing to allow our leaders to use our pain as a weapon against Palestinians.”

Later that day, a State Department official in the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs resigned in protest of the Biden administration’s approach to the conflict. “The fact is, blind support for one side is destructive in the long term to the interests of the people on both sides,” he wrote in a letter posted on LinkedIn. “I cannot work in support of a set of major policy decisions, including rushing more arms to one side of the conflict, that I believe to be shortsighted, destructive, unjust, and contradictory to the very values that we publicly espouse.”

Speaking with moral clarity is difficult and may become more difficult in the days ahead. But justice, freedom, and safety — for Palestinians and Israelis alike — will depend on more than saying the right things. It will require courageous acts like these.

More on the israel-hamas war

- Why Universities Have Started Arresting Student Protesters

- For Biden, Standing Up to Netanyahu Would Be Pro-Israel

- Eric Adams Applauds NYPD After Violent Arrests of Pro-Palestinian Demonstrators