This article originally appeared in the August 1988 issue of Esquire. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

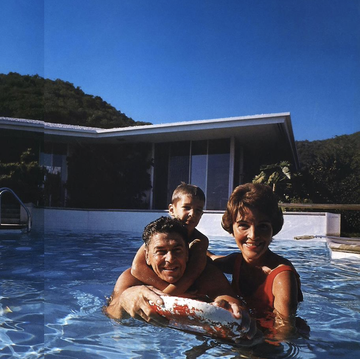

When he wants to, Robbie Robertson can disarm you with his candor. Ask him why he stopped making records for ten years, and the creative force behind the Band—the man who wrote “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”ߞwill tell you, ‘‘I didn’t have anything else to say.” Ask him how he ended up in L.A. and he’ll tell you, “I was doing a lot of work in films . .. and I’m not crazy about planes.” But when he starts describing his recording-studio workshop as containing “only the bare essentials,” your skepticism begins to stir. Press the issue and you’re likely to get the impenetrable look the generally genial guitarist reserves for the camera. After too many years in the business, he’s learned what it takes to do his job.

“For years I wrote all night long, in delirium. I would just grind them out, pulling teeth, bashing my head against the table.” But this time, when the songs started to flow again, instead of checking himself into a motel as he’d done in the past, he checked directly into this studio, where he labored for two years. “Some amazing records have been recorded in this room.” He’s not kidding—Ray Charles, B. B. King, Sly Stone. And if anything less than this studio would have kept him from adding his own stunning self-titled comeback album to that list, then indeed, this place is essential.

But it is a different type of artist whose presence is discernible in Robertson’s studio these days. For while he was lying low, he became a collector of modern American Indian art. To his left hangs a piece by Darren Vigil, a young artist from the southwestern bohemia of Taos, and behind him, one by Arizona artist C. J. Wells. “In the past everybody felt a lot of guilt about the Indian people. But in these young artists, I get a very stout, dignified feeling.” In the word stout you hear his Canadian roots. But what his accent won’t reveal is that he himself is half Iroquois. He’s cautious about his connection to the movement, though. “I’m a breed,” he says. “These people are all blood. I don’t want to be wagging someone else’s flag.”

When you ask about the guitars, fatigue creeps into his voice. “Yeah, I’ve got guitars at home, I’ve got guitars upstairs, you know, a guitar here, a guitar there.” But he keeps his favorites here: the Stratocaster he had bronzed for The Last Waltz; a rare double-necked Gibson guitar-mandolin; and the old Broadcaster he picked up before the Band’s ’74 tour with Dylan.

Ultimately, the paradox is too obvious to go unspoken: How is it that a man whose songs are so rooted in the earth finds asylum in a windowless box in the middle of a sprawling, synthetic city? But he’ll let you push him only so far before his candor wins out again and he brings the whole conceit crashing down. For the greatest stimulus to his writing is not the paintings, nor the guitars, nor the aura of musicians past, but the four walls themselves, an inescapable reminder of the mission that brings him here. “It has nothing to do with atmosphere,” he finally says. “It has only to do with my imagination.” And for all your trouble, could you have expected anything else?