Is cask ale right wing, left wing, both, or neither? Is cask, in American terms, ‘conservative coded’? It’s complicated.

Last week a row blew up when an industry body concerned with cask ale announced plans to promote its newest campaign on the right wing GB News channel.

The controversy was more intense, perhaps, because this happened in a week when even GB News seemed to concede that some of its presenters had gone too far.

Observing this news from across the Atlantic, American drinks writer Dave Infante asked for context via social network BlueSky:

any british drinkers on here that could weigh in on how ‘conservative’ cask ale is coded in the uk?

Travelling on a bus across Somerset, we did our best to answer in a series of quick replies.

But, actually, this feels like a topic worth digging into in more detail, and now we’ve had more time to reflect.

What do you mean by ‘cask ale’?

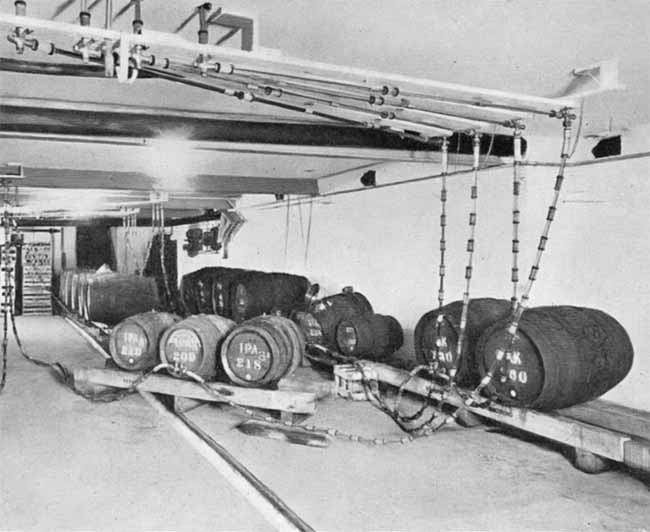

Literally, cask ale refers to a method of dispense, as explored in-depth by Des de Moor in his most recent book.

But here, we’re talking about its place in British culture. What it means, or signifies.

For many people, cask ale is synonymous with brown bitter, produced by companies hundreds of years old, such as Arkell’s or Shepherd Neame.

It’s horse brasses, Inspector Morse, dimple mugs, shire horses, blazers with badges, regimental ties, red trousers, vintage cars, cricket, golf, Alan Partridge with his big fat shot of Director’s.

A pint of your finest foaming, if you please, stout yeoman of the bar.

This version, or view, of cask ale is distinctly ‘conservative coded’, for one particular idea of what conservatism means.

What do you mean by ‘conservative’?

In Britain, as in the US, conservatism is fractured.

The Conservative Party, AKA the Tories, was for many years the party of the landed gentry, the military and the Church.

They were literally conservative, as in, resistant to social change, and supportive of existing social hierarchies.

Then, in the late 20th century, the Conservatives pivoted under Margaret Thatcher to a more radical form of conservatism.

It prioritised deregulation, low taxes and free market economics, with less emphasis on social class and tradition.

Especially if it got in the way of growth.

You might almost categorise these two factions as (a) cask ale Tories and (b) lager lout Thatcherites.

The latter group, to deal again in broad stereotypes, were less about shire horses and tweed, more Porsches and pinstripes.

There’s no doubt that the late John Young of London brewery Young & Co was a conservative.

Indeed, it’s been suggested he was somewhat further to the right than that gentle word might suggest.

He was also a dogged traditionalist who clung to cask ale throughout the 1970s, arguably playing a large part in saving it.

Then, on the other hand, you might look at the families behind Watneys, Whitbread and the rest of the Big Six.

While supporting the Conservative Party, they were entirely unsentimental about cask ale.

In pushing keg bitter, then lager, throughout the post-war period, they were regarded as the enemies of cask ale.

It was in that context that the script got flipped and cask ale became an element of the counterculture.

Cask ale as a radical cause

Whether the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) was left or right wing was something we researched in depth a decade ago while writing Brew Britannia.

Early members of the campaign included “everyone from National Front members to Maoists”, as one interviewee told us.

People who wanted to preserve tradition and turn back the clock found themselves campaigning alongside those who wanted to give Tory brewery owners bloody noses and champion ‘small is beautiful’ principles.

Broadly speaking, though, CAMRA was about challenging powerful capitalist interests (Watneys) and was sometimes talked about as a sort of beer drinker’s trade union.

It seems to us that many of the newer generation of microbrewers shared this rebellious, challenger mindset, even if their owners’ personal politics varied widely.

In the 21st Century

As we keep saying, cask ale’s political image is complicated, and only got more so in recent years.

As ‘craft beer’ arrived in the UK, cask ale came to be regarded by some as a relic, and CAMRA as an obstruction.

Self-declared rebels and revolutionaries like BrewDog (we know, we know – check out chapter 14 of Brew Britannia) made keg beer their cause.

For a stretch there, that meant even small scale cask ale was perhaps regarded as ‘conservative coded’.

Even though BrewDog, Camden and other successful keg-focused UK craft breweries proved to be the most purely capitalistic of the lot.

And much to the irritation of radically-minded cask ale brewers, especially in the North of England.

But in these days of the supposed culture war ‘conservative’ isn’t just about your attitude to economics. It’s also about your stance on feminism, gender, racism, Brexit, vaccination…

Nigel Farage, the most prominent champion of Brexit, made pints of cask ale part of his personal image, and the preservation of the crown-stamped pint glass a key talking point of the ‘Leave’ campaign.

As beer writers are fond of pointing out, cask ale is uniquely British (terms and conditions may apply) and so lends itself to nationalist posturing.

Cask ale is also associated with ‘proper pubs’. For many, a proper pub is the very dream and ideal. For others, it’s an idea loaded with danger signs: doesn’t it just mean white, male and possibly, or probably, racist?

CAMRA has also struggled to convincingly counter suggestions that racism and sexism are baked into its culture – though perhaps headway is finally being made on that front, at the cost of alienating members who liked that.

One final test

If you were writing a fictional character who is a conservative (right wing) what would you have them drink?

Depending on the flavour of their conservatism, it might be Champagne, wine, port or brandy.

If they’re a filthy rich City type, they might go for the most expensive lager on the bar – or a keg IPA, these days.

But in most instances, it would be a pint of cask ale, right?

That’s certainly what Conservative Party politicians like to be photographed holding, even when they don’t drink.

Look, we know it’s almost a decade old, but do give Brew Britannia a read. It goes into much of the above in plenty of detail and should help you work out your own answer to this complex question.